Many years ago, I attended the very first Lean startup workshop hosted by Eric Ries. We were his guinea pigs in a true MVP (Minimal Viable Product) experience. It was an amazing event that shaped my mental model of building startups and pursuing Product/Market Fit.

Since then, I’ve had the opportunity to be a part of multiple Zero to one startups from incubation through growth stages and acquisitions. I’ve seen a few successes, and I’ve failed a ton along the way. My biggest learning as a product and technology leader would be to echo the wisdom of the great philosopher, Weird Al Yankovic: “Everything you know is wrong”. Or, as Marty Cagan eloquently captures as the “Two Inconvenient Truths About Product”:

“The first truth is that at least half of our ideas are just not going to work…The second inconvenient truth is that even with the ideas that do prove to have potential, it typically takes several iterations to get the implementation of this idea to the point where it delivers the necessary business value.”

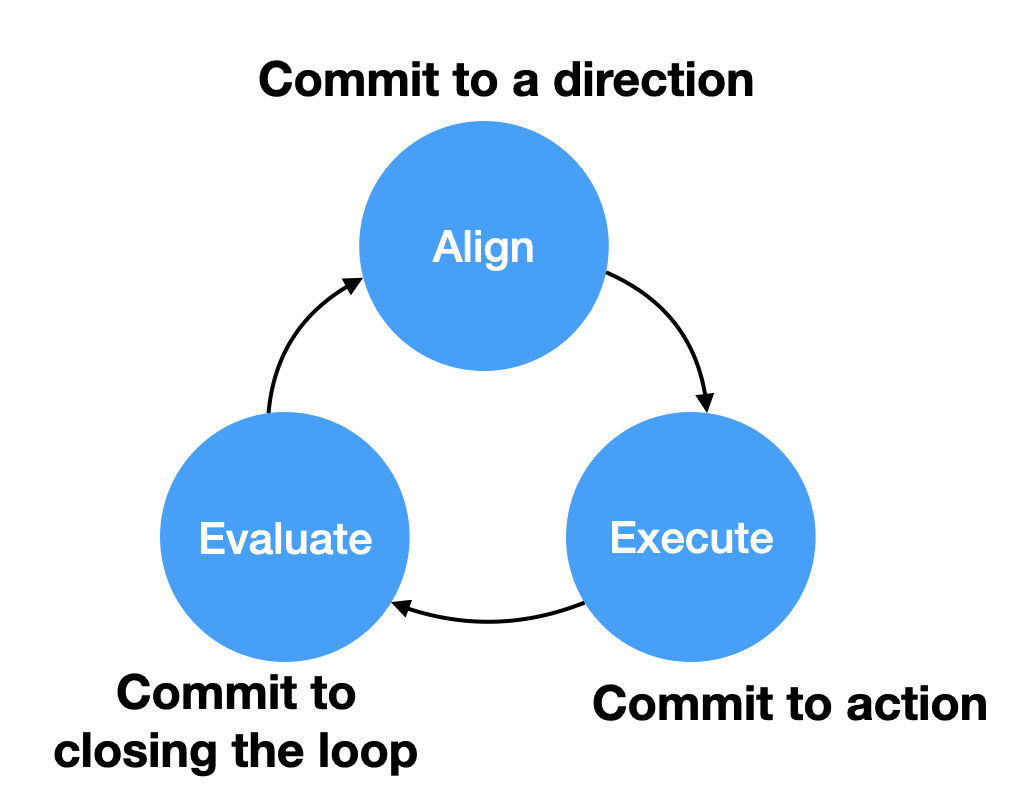

Time is the enemy of every startup, and the best way to increase our odds of success is by having our customers tell us what matters to them as quickly as possible (and what doesn’t matter). The tighter our feedback loops, the more opportunities we have to iterate and get it right for our customers. I’ve taken a few concepts that have been useful for me and refined them into a Product Development Process (PDP) called “The Commit Cycle”.

First, we need to know where we are headed. We commit to a direction.

Our direction is set by working backwards from what success looks like for our customers, and the necessary steps to get there. Defining our plan should take as little time as necessary (and yes it is necessary).

The three critical elements of the direction include:

- Scope of work. There are a million frameworks to choose from (my personal favorite is User story mapping), but at the end of the day, pick one that works for your team, and consciously evaluate how to improve it later.

- Success criteria. What is the impact are we trying to accomplish for our customers and company? How will we look back on this plan to know that we were successful?

- Timeline to close the loop. Timebox execution until we will pause and reflect as a team.

Now that we have our direction, we can put our heads down and execute. We commit to action.

The key to execution is to minimize time not spent executing. The four most impactful tips to improve execution are:

- Avoid interruptions. Be intentional in how you structure your time to optimize for effective Deep work.

- Defer changes. Changing priorities are one of the biggest reasons for loss in velocity. As much as possible, defer additional changes to the next iteration. The tighter our feedback loops, the easier it is to defer incoming work to “the next version”. If the feedback loop with our customers takes months, it’s significantly more likely that incoming requests will be added to the current scope of work.

- Kill latency in communication. When decisions must be made, and roadblocks uncovered, the time to resolution is the most important thing to optimize for. My personal “Rule of 3” protip for async communication is that when you hit 3 back-and-forth messages on a specific topic that remains unresolved, you must escalate to synchronous communication (video/phone/etc).

- Minimize coordination taxes. Dependencies on other teams may be not be possible to eliminate, but it may be possible to minimize by taking on certain workstreams within your team (even if it takes ramping on new subjects and technology) to unblock yourselves.

As execution wraps up, we pick our heads up and commit to closing the loop.

The most telling sign of a high-performing team is the quality of their retrospectives. If a team completes a retrospective with a general sense that “we’re all good” with no areas for improvement, I just plain don’t believe them. Every high-performing team invests time in reflecting on their work and consciously making changes to improve. Craftsmanship has no upper bound, and Bob Iger’s leadership principle has been an inspiration to constantly be “in the relentless pursuit of perfection”.

Closing the loop requires that we reflect on our commitments in four specific areas.

- Reflect on the plan.

- Did we complete what we committed to? Review the acceptance criteria of each item collectively to inspect if the work is really complete (this may be harder than you think).

- Where did we underestimate and overestimate the amount of time things would take?

- Reflect on the execution.

- What disruptions did we encounter? interruptions/dependencies/collaboration tax did we encounter?

- How much Deep work did we have?

- Discuss the quality of the work produced. Are we proud of our work?

- Reflect on the impact.

- Did our work have the impact we expected? Why, or why not?

- What have we learned from our customers?

- How are the systems performing in production?

- Reflect on the process.

- What could we do to make the next commit cycle tighter?

- Is our planning and retro process working for us?

That’s it! Now, we ingest these learnings into our plan for the next Commit Cycle and keep on rocking!